This isn’t the article that’s gonna explain merge vs rebase for people that haven’t used git before (sorry). Rather, this is gonna be about some more meta things for maintainers, release engineers, and other people who care about development process.

Git gives you a lot of options. How you use it isn’t prescribed in advance. There are a lot of ways that people might use git differently, but here, I’m more seeking to investigate some of the ways of using git that are relevant to people in charge of git repositories with a non-trivial amount of contributors, like myself.

While I enjoy having these things done differently between projects I’m working in and part of maintaining — as it gives some diversity to the methods I get to use in my work, and let’s me continuously evaluate multiple methods[1] in practice — I do think it makes sense that for a single project, there is consistency in the way it’s developed, so that expectations can be set, and procedures can be learned and become second nature.

There are two main questions for a project to decide when it comes to merging via git.

- How to merge feature branch changes from PRs.

- How to merge newest changes into outdated branches.

I’ll discuss both, and then summariese my observations.

Merging branches

When some developer starts working on a software feature, especially in open source, those changes, typicall, will be made in a separate branch that has branched off from the main branch. This is often called a feature branch. This allows the developer to work on their feature in isolation, and, at some point, put those changes back into the main branch, for all people to use.

This is what some may call trunk based development, although the lines get fuzzy about how long a PR should live. That discussion is out of scope for this post, but I’d love to follow up with a post about that at some point.

When moving changes from your feature branch into main, you can have potentially three possible options for merging.

- Fast Forward

- Rebase and Fast Forward

- Merge

For fast forward, main may not have changed while you were working, and so you can “fast forward” your changes on top of main, without having to worry about any conflicts. This is, for both developers and maintainers, extremely easy, with some reservations that will be discussed later.

Another option is to take the changes from the updated main branch, and git pull --rebase origin main them into your feature branch, placing your changes on top of the latest changes from main. As you may guess, this allows you to git merge --ff-only your changes into the main branch.

The final strategy is the classical merge. You may decide to merge your changes, and the changes in main together, using a special commit that represents the operation of merging the two together, a merge commit. Such a commit has special properties, such as having two parents, and being the result of the unification of two separate branches.

Of course, if you’re not doing just a simple fast forward, either a rebase-ff or merge may require that you solve potential code conflicts. For instance, someone may have changed a line that you have also changed, leading to the two versions colliding. For the merge, you resolve this by making the merge commit define the merged version, for a rebase, you’ll go through your changes and adjust them so they fit cleanly onto the branch you’re pulling.

One important difference to note for us, is between the two, merging into main typically gets done by the maintainer, where as rebasing gets done by the developer working on the feature branch.

Rebasing also has some downsides. For example, if the person rebasing doesn’t have the PGP private key of the people who’s commit are included in the rebase, they cannot sign the commits. This means that if Alice made 3 commits and signed them with her PGP signature, Bob can’t later rebase those changes onto some other commit without breaking that signature. This is because, while the code doesn’t change, the commit revision does, and so the signature is wrong.

Merging does not have this issue, as a merge is simply the actual merge commit, containing the new state of the branch, that potentially specifies how to rearrange everything so as to not cause any conflicts. Thus it doesn’t suffer from breaking the signatures.

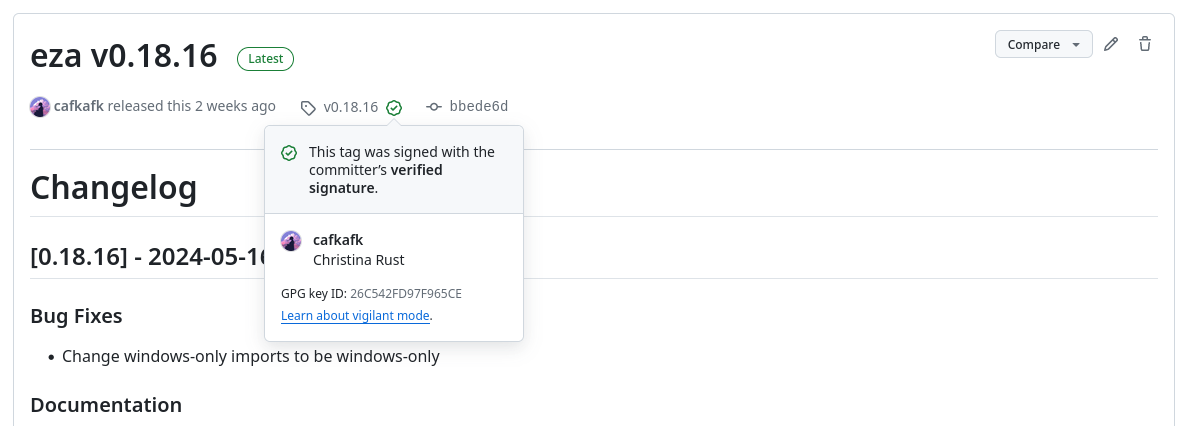

Now, if you’re using rebase for merges into main, as we do in eza, you may still want a signature verifying that a trusted person has indeed verified these changes are up to whatever standard they guarantee (eza at best guarantees that it runs on my linux box that you should be able to install it on NixOS[2]). The way we solve this is by tagging all our releases with a signed tag, making sure you know that I’ve personally said that this is the codebase I want you to run for a given release.

But even then, it’s coping. It’s not as nice as having a tree full of the signatures of everyone that’s committed, right on their commits.

Another point raised against rebases is they rewrite history. This is true,

unlike a merge that just merges two branches and keeps both in history, the

rebase will make it appear as thou the feature branch was developed on top of

the main branch. I don’t personally think this is a huge concern, except the

loss of potential pretty git log --graph outputs.

One of the annoyances of merges, in comparison, is that they’re very noisy. Consider this output from nixpkgs:

| |

This… isn’t nice, and makes history way harder to read. Compare to eza:

| |

Isn’t that a lot nicer? I think so.

Of course, what may be lost is that it’s no longer obvious from what PR a change originated. It also isn’t obvious to me when some feature branch was created, how long it was worked on and so on. This isn’t… really that important either, but it’s nice to have in logs. But you can just look at branches if you need to know this for tooling or something.

For nixpkgs, you get a to have a visual overview of how branches end up in main. It looks like this:

| |

Another problem worth considering is that a rebase may — as

Astrid pointed out — results in main being in a state

where a git bisect of a build command may fail, if you haven’t ensured that

all commits in the feature branch still worked after being rebased on top of the

latest main.

Now this is rare, but rare isn’t really a good argument for not caring here, as

breaking once would be extremely annoying for people working on a bugfix,

leading to false git dissect positives.

There are solutions to this. You could (perhaps) have each commit in a branch

run against CI. This may be outside of your compute budget thou. Another option

is to run your build command, e.g. cargo build on each commit after a rebase,

but then, this kind of checking step usually falls on the maintainer, and we, as

maintainers, should seek to limit our own burdens as much as possible (to

prevent burnout[3], the killer of most FOSS projects).

To eza, this isn’t fatal, but a very interesting point worth keeping in mind.

Updating a branch

Of course, since there may be multiple people all working on separate branches, there is another problem. One person might have worked on something, at the same time as you worked on something else, and then gotten their changes merged before you had a chance. But if that happens, your changes might now conflict with what was in the main branch when you started, and worse, their changes may make ruin your work, or even make it unable to compile!

The first choice a project should make, is whether or not to allow outdated feature branches to be merged. The problem with tolerating outdated branches is you will not be able to fix any problems related to integrating the code with the main codebase before merging it. This puts the burden of ensuring the code works on the maintainer, rather than the developer, and this is bad!

If you do choose to not allow this, another question faces you: how should the main branch be merged into the feature branch when the feature branch is out of date with the main branch.

Your options are either to merge the main branch into your feature branch, or to rebase your changes on top of main, making it like if you had started working on the latest changes.

To me, it’s a more simple dilemma, merges shouldn’t exist if they don’t meaningfully represent merging two things together. Simply updating your branch is what rebase does best, and having merges both from feature branches into main and from main into your feature branch is absolutely tasteless. This clutters your history for no reason. It also makes it harder for you to fix your commits when the reviewer tells you that you had a faulty commit 3 commits before you merged main into your feature branch and kept working for 4 more commits.

In general, rebasing with merge commits is tedious, and we only consider merges viable for the main branch under the premise that we won’t later need to rebase main, because everything that gets into main is in a state of being up to standard.

Sadly, code forges lack a feature to only allow updating branches with the projects preferred standard, unlike for merges where rebase, squash, and merge are all options, that all can be disabled by the repositories owner(s).

Summary

So what where the tradeoffs?

- Merging feature branches into main

- Merges.

- Preserves history.

- Gives you

git log --graph. - Doesn’t break PGP signatures.

- Creates ugly

git log. - Gives weak protection that all commits build (if you have CI)

- Puts burden of verification on maintainer.

- Rebase.

- Rewrites history.

- No

git log --graph. - Breaks PGP signatures.

- Creates useful

git logoutput. - Needs more care if you want all commits to be validated.

- Puts burden of verification on committer (mostly).

- Fast Forward.

- Like a rebase, but with less drawback.

- Merges.

- Updating your feature branch.

- Merges.

- merges make

git rebase -idifficult, when asked to change your commits. - It makes your

git logunreadable. - Doesn’t provide any benefits.

- Mostly just a quirk that git even allows this, it doesn’t make sense.

- merges make

- Rebase.

- The preffered choice.

- Fits like a glove for updating your feature branch.

- Merges.

As a maintainer, remember that what where really trying to do if offload any non-maintainer burdens onto relavant roles, like developers and reviewers. We may wear multiple hats, often we are the final reviewers, but even then, it shouldn’t be our job to ensure a clean merge, we should meerly verify it.

The main goal is always: maintainers shouldn’t need to fix the feature branch!

Footnotes

[1]: This also applies for formatters. I personally mostly use alejandra for nix, but dayjob uses nixfmt (the RFC 166 version). I just hit a format button before commiting anyways, so it’s just cool to see the different options and feel out which ones I truly prefer.

[2]: Because I don’t have any MacOS, Windows, or BSD boxes to test on, and we don’t have any maintainers that do with the spoons to be involved in giving such guarantees.

[3]: Consider reading this excellent resource https://opensource.guide/maintaining-balance-for-open-source-maintainers/, and this mozilla worksheet https://docs.google.com/document/d/1esQQBJXQi1x_-1AcRVPiCRAEQYO4Qlvali0ylCvKa_s/edit?pli=1#heading=h.xd8n2v3f4866.